I talked with Hayley Matthews at DatingAdvice.com about the implications of some of my recent research for online dating. Great article! Check it out here.

Category: Media Coverage

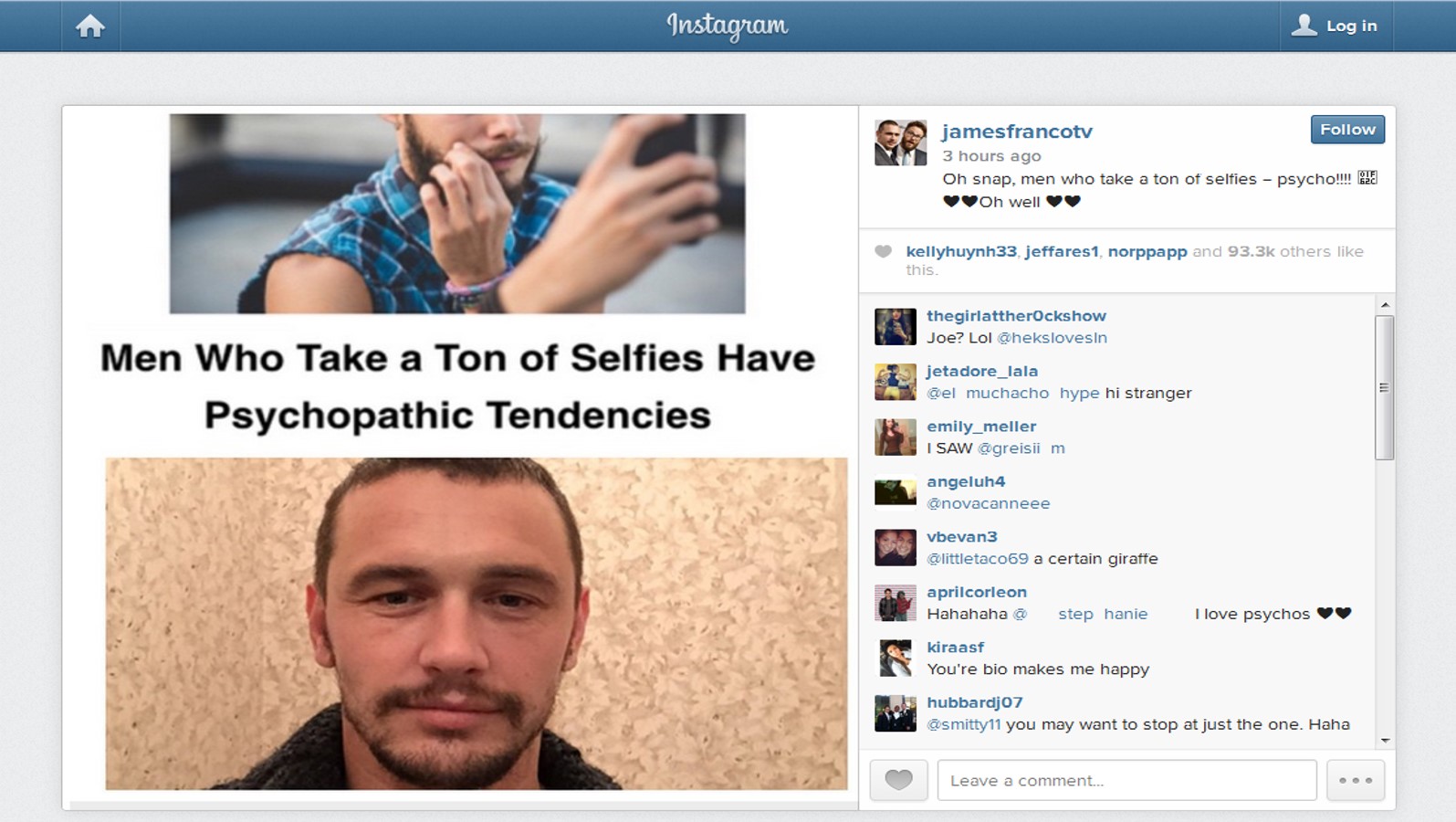

A recent study on selfies I published with my awesome Ph.D. advisee, Margaret Rooney, was picked up widely in the mainstream media this past week. Not unexpectedly, there was cheeky but accurate news coverage (e.g., CNN, Health,and I liked this video from the Chicago Tribune), appropriately measured coverage (e.g., Jezebel, a fellow blogger at Psychology Today), and awful, panic-stricken, inaccurate drivel accompanying splashy clickbait titles (too many tabloids and blogs to name). (Update: I’m also ecstatic to report it made The Onion.) I’m a bit behind the ball here but, in the name of good science and accuracy, I wanted to provide some answers and clarifications.

A recent study on selfies I published with my awesome Ph.D. advisee, Margaret Rooney, was picked up widely in the mainstream media this past week. Not unexpectedly, there was cheeky but accurate news coverage (e.g., CNN, Health,and I liked this video from the Chicago Tribune), appropriately measured coverage (e.g., Jezebel, a fellow blogger at Psychology Today), and awful, panic-stricken, inaccurate drivel accompanying splashy clickbait titles (too many tabloids and blogs to name). (Update: I’m also ecstatic to report it made The Onion.) I’m a bit behind the ball here but, in the name of good science and accuracy, I wanted to provide some answers and clarifications.

The short summary: we used data from an online survey of 800 nationally representative U.S. men aged 18 to 40. The survey asked them about social media behaviors and personality traits among some other items. We were interested in the relationship between some traits (the Dark Triad and self-objectification) and social media behaviors. We found:

- Self-objectification and narcissism predicted the amount of time men spend on social networking sites.

- Narcissism and psychopathy predicted the number of selfies men post on social networking sites.

- Narcissism and self-objectification predicted men’s editing of photos posted to social networking sites.

Here are some commonly asked questions as well as some clarifications about the study.

What is The Dark Triad, anyway? Sounds like a goth band.

These are what we refer to as antisocial personality traits. On the whole, these traits are associated with some pretty nasty behavior. Those high on the Dark Triad are manipulative, callous toward others, and often use deceit to get what they want. They focus on achieving their own goals, even when those are at the expense of other people.

Antisocial traits? But they’re using social media. Isn’t that social?

“Antisocial” doesn’t mean necessarily mean unwilling to associate with others; here it means these traits aren’t prosocial or beneficial for society. Dark Triad individuals are usually pretty adept at getting what their social needs fulfilled, but this is without regard for others. Social networking sites might help them meet those goals. Laura Buffardi and W. Keith Campbell published one of the first pieces on narcissism on social media in 2008, and several others have followed up with similar investigations. I would also recommend Dr. Chris Carpenter’s (2012) study, which identified specific behaviors narcissists exhibit on Facebook; this study that linguistically analyzed Facebook posts for indicators of Dark Triad traits; and Peter Jonason’s fascinating work on Dark Triad traits and interpersonal behavior more generally (e.g., here and here).

So, you found that narcissism predicts selfies. Um, #duh?

Admittedly, I wasn’t as interested in narcissism as I was the Dark Triad trait of Machiavellianism, which is characterized by being manipulative and amoral. I’ve identified relationships between Machiavellianism and other social media behavior, but it didn’t predict men’s selfie behaviors.

So, why is this finding still important? Well, first, just because something seems like common sense or something is commonly accepted doesn’t mean it’s scientifically accurate. Remember the good ol’ days when bacon (hey, protein!) and smoking (so relaxing) were good for you? Scientists have to confirm even the obvious stuff because sometimes there’s more going on than we think (which was the case here when you think about the roles of psychopathy and self-objectification.)

Second, the narcissism finding is a bit more interesting than it seems on face. The common understanding of narcissists is that they are self-absorbed, egocentric, entitled, and think they’re better than everyone else. This is accurate, but there is another important aspect of narcissism: an underlying insecurity. The selfie finding is interesting to me because it implies that narcissistic individuals may post selfies to address this insecurity. As I discuss in this paper, many social networking sites allow people to get comments, “likes,” and other forms of social feedback, and narcissists in particular may rely on these features (or affordances, if you want the scientific term) to make them feel better about themselves.

He posted a selfie! OMG! Is the guy I’m dating a psychopath?

Deep breaths. In this study, we measured the subclinical (i.e., normal) range of these Dark Triad traits. Everyone has a little bit of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism in them. Yes, even you. We can’t draw conclusions from these data about clinical levels of psychopathy or what people would commonly describe as a “psychopath.” So, don’t believe the hype.

This isn’t to say subclinical psychopathy is a desirable trait, however. It is characterized by impulsivity and a lack of empathy for other people. People higher in psychopathy may post selfies online impulsively and without thinking. (It makes sense, too, that we didn’t see a relationship in between psychopathy and editing your selfies given this impulsivity.) Because people higher in psychopathy lack empathy, they might not care if you’re annoyed by all the selfies they post, either.

I told ’em! This generation! All them Facebooks and selfies are turnin’ those kids into narcissists!

This study was a survey, which means we can’t make any causal claims; experimental research is needed to answer those questions. Narcissism could cause selfies, or selfies could cause narcissism, or a third variable could be driving them both. We can only state that we observed a relationship between these things among a nationally representative sample of U.S. men aged 18 to 40.

Well, how many selfies can I post without looking like a total narcissist?

We only looked at selfie posting in this study. We don’t have enough research on how people perceive others’ selfies yet to answer this question. My common sense answer: if you have to stop and ask yourself if you’re posting too many selfies, you are probably posting too many selfies. My suggestion is to ask your close friends what they think about the frequency and content of your selfie posting–and don’t get defensive when they give you honest feedback.

Why did you only look at men, hater? Obviously it’s because you are female and out to get men.

Ah, the stupid, sexist things trolls say. Read the paper. Magically, the answer is there. The longer story:

Trust me, I would have loved to have a nationally representative sample of women as well, but I had no control over what went in the survey. Glamour magazine conducted the survey through a survey company. Most survey companies charge by chunks of time (e.g., 20 minutes) and you get to fill those minutes with questions. As a women’s magazine, of course they had more questions to ask the women, and they filled the women’s 20 minutes with other questions. (You can see the results in their November 2014 issue.) They had some time left over on the men’s side of the survey given they didn’t have to ask men about their thigh gaps and bikini bridges, and so they included the Dark Triad and self-objectification measures. Thus, no data on the Dark Triad or self-objectification for this particular sample of women.

Don’t fret, though. I already have data collected on women, and the results are coming soon. The problem is that a nationally representative sample is very expensive, so I collected data with a convenience sample of college women. This means the sample will be restricted in age, education, and race/ethnicity, unlike the men’s sample. So, we can’t be as confident that these data will represent U.S. women as a whole, but it’s a start in answering questions about women and selfies.

Anyway, that’s all I wanted to add except an additional thanks to Liz Brody, Shaun Dreisbach, and Glamour for making this research possible, and to Jeff Grabmeier, Joe Camoriano, and OSU University Communications for helping with the media traffic. It’s an academic’s dream to work with so many great people in so many different research-related contexts.

Just in time for VD (Valentine’s Day), I did an interview with CBC Radio’s Nora Young. We talk about how technology has changed the dynamics in romantic relationships and more specifically how techno-incompatibility can cause conflict between partners. Listen here.

This morning started off with another media-induced facepalm. Thanks to Owen Good at Kotaku for drawing this to our attention.

One of the downsides to being a scientist is having your work misrepresented in the media. It’s bad enough when you can tell they write a report or story based on another story that’s based on another story. Worse is when they bring in “experts” to sensationalize it (especially when they don’t bother contacting the actual researchers for an accurate statement.) Fox News aired a segment on my recently published study on the negative effects of sexualized avatars. Here is what is wrong about it.

1. They say we studied “young girls” and the discussion is around children. We studied female adults (none younger than 18), which is clearly noted in the article.

2. At another point, they say we studied “gamers.” Video game play varied among this sample; participants reported playing between 0 and 25 hours of games a week (M = 1.29, SD = 3.70). Also, they were not asked if they self-described as gamers.

3. Participants did not choose avatars for this study; they were randomly assigned to assure the validity of the manipulation. (Read this if you don’t understand the importance and implications of random assignment for experiments.) I am researching choice in other studies because there could be a self-selection bias in play when it comes to gaming (e.g., women who self-objectify may be more or less likely to choose sexualized avatars).

4. The simulation was not a video game. It was an interaction with objects in a fully immersive virtual environment and a social interaction with a male confederate represented by an avatar. Further research with gaming variables is necessary because those sorts of elements change outcomes in unexpected ways, as my grad student Mao Vang and I recently found when we had White participants play a game alongside Black avatars.

5. What is most wrong is that their “expert” is not a scientist or even a gaming researcher, but a self-described life coach. I looked her up and she has zero notes on her website about her scientific education or experience. Rather, it is a business site populated with slogans like “Let’s Get it, #Go and MAKE THAT DOUGH!” (Random hashtags, arbitrary capitalization, and outdated slang all preserved from the original.) There’s no indication that she knows anything about science, virtual environments or video games, or girls’/women’s development or psychology. It’s clear from her interview that she did not read the article–I love that Owen Good at Kotaku points out that she swipes lines from another journalist’s writeup at Time.

Perhaps the most egregious transgression is when she puts words in our mouths with this gem: “But they say that this is, like, even worse than watching Miley Cyrus twerk.” NO, WE DIDN’T SAY THAT. NOR WOULD WE. EVER. That statement was made by the Time reporter and was rightfully not attributed to us.

Such are the frustrations of the scientist.

Given the recent media attention, I figured it would probably be wise to give a rundown of our experiment recently published in Computers in Human Behavior on the negative consequences of wearing sexualized avatars in a fully immersive virtual environment. Although several media sources are framing this as a study involving video games, there was no gaming element to it (although I expect the findings to apply to video games, there are different variables to consider in those settings).

A fully immersive environment. The user is in a head-mounted display (HMD) and can only see the virtual world, which changes naturally as she moves.

This study was conducted while I was still at Stanford working in the Virtual Human Interaction Lab. I conceived the study as a followup to a previous study whose results had confounded me. In that study (published in Sex Roles), men and women were exposed to stereotypical or nonstereotypical female virtual agents, and we found that stereotypical agents promoted more sexism and rape myth acceptance than nonstereotypical agents. I was surprised because we found no difference between men’s and women’s attitudes. Thus, I wanted to investigate further to see how virtual representations of women affected women in the real world.

In the current experiment, we placed women in either sexualized or nonsexualized avatar bodies. We used participants’ photographs (taken several weeks before for a presumably unrelated study) to build photorealistic representations of themselves in the virtual environment. Thus, when a woman entered the VE, she saw her face or another person’s face attached to a sexualized or nonsexualized avatar body.

In the virtual environment, women performed movements in front of a mirror so that they could observe the virtual body and experience embodiment (i.e., feel like they were really inside of the avatar’s body). They had a brief interaction with a male avatar afterwards and then we measured their state self-objectification (through the Twenty Statements Test, which is simply 20 blanks starting with “I am ______”). Then, we told them they would be participating in a second, unrelated study. They were allowed to pick a number that “randomly” redirected them to an online study. All participants were redirected to “Group C” which was framed as a survey on social attitudes. The rape myth acceptance items were masked in a long survey with other items.

We found that women who embodied a sexualized avatar showed significantly greater self-objectification than women who embodied a nonsexualized avatar. Furthermore, and counter to predictions, women who embodied an avatar that was sexualized and looked like them showed greater rape myth acceptance.

This second finding was puzzling; I thought seeing oneself in a sexualized avatar would make participants more sympathetic. Our best explanation was that perhaps that seeing oneself sexualized triggered a sense of guilt and self-blame that then promoted more acceptance of rape myths.

Since this study I have conducted two other studies (both using nonimmersive environments to make sure that it is not just the high-end technology yielding these results) that support these findings. Feel free to contact me if you’re interested in those papers.

You can find media coverage of this study at the links below:

*Original story by Cynthia McKelvey for Stanford News Service (also posted at PhysOrg)

* Video Games’ Sexual Double Standard May Have Real-World Impact by Yannick LeJacq at NBC News

*How Using Sexualized Avatars in Video Games Changes Women by Eliana Dockterman at Time

*Using a Sexy Video Game Avatar Makes Women Objectify Themselves by Shaunacy Ferro at Popular Science

*The Scientific Connection Between Sexist Video Games and Rape Culture by Joseph Bernstein at Buzzfeed

Interestingly, the media have just picked up on a study published earlier this year that I ran while I was still at Stanford. Co-authored with my advisor, Dr. Jeremy Bailenson, and undergraduate research assistant Liz Tricase, the study found negative effects for women who embodied sexualized avatars in a fully immersive environment. Jeremy saw the article online at phys.org and captured this screenshot. *facepalm*![]() (Note the ad to the right, telling you to “Create Your Hero Now.”)

(Note the ad to the right, telling you to “Create Your Hero Now.”)

The article itself is an excellent writeup by Cynthia McKelvey. Feel free to check out the study itself here.

Social networking sites provide unprecedented access into the lives of our friends, family members, strangers, and current and former romantic partners. Much of my research investigates whether or not this is a good thing. (Spoiler alert: it’s not.)

In a recent study with Dr. Katie Warber at Wittenberg University, we explored how an individual’s attachment style and level of uncertainty about their relationship (current or recently terminated) predicted their use of Facebook to “cyberstalk” their partners. (Academically, we prefer the term “interpersonal electronic surveillance.”)

Attachment theory suggests that our adult relationships are influenced by our relationships with our parents as infants. Depending on how that bonding process went, we experience varying levels of avoidance (the degree to which we seek or avoid close relationships) and anxiety (the degree to which we are uneasy or overly concerned about our close relationships). Individuals who are low on avoidance and anxiety are considered secure in their relationships. Those who are high on avoidance and low on anxiety are dismissive. Low on avoidance and high anxiety individuals are preoccupied, and those high on both are deemed fearful. These attachment styles predict a number of behaviors within romantic relationships.

In this study, we looked at both people currently in relationships and those in recently terminated relationships. We also examined the role of uncertainty. Surprisingly, uncertainty about the relationship did not play a role in surveillance. Rather, we found that preoccupied and fearful attachment styles engaged in significantly more surveillance.

Given preoccupieds are insecure about the relationship and low on avoidance (hence, a tendency to be clingy), we expected them to have the highest levels of Facebook stalking. It is interesting that fearfuls were also higher, however, given they tend to be high on avoidance. One possible explanation is that even though they are getting information about the partner, Facebook stalking enables fearfuls to still avoid direct interaction with the partner.

There remains a lot to explore with attachment theory, romantic relationships, and social media. I hope to have some more findings in this area available soon. In the meantime, you can check out the article (linked below) or oft-snarky media coverage at Slate and Jezebel. There is also a brief writeup and interview available at United Academics.

Fox, J., & Warber, K. M. (in press). Social networking sites in romantic relationships: Attachment, uncertainty, and partner surveillance on Facebook. To appear in CyberPsychology, Behavior, & Social Networking.